Once upon a time, in a land called Daventry, a humble knight with a feather in his cap set out to find three stolen treasures. One was a magic mirror that could reveal the future. Another was an enchanted shield that protected its bearer from harm. The third was a chest of gold that never emptied. In the name of adventure, the knight woke sleeping dragons, outwitted angry trolls, and climbed impossible staircases—all to help the king keep Daventry at peace. As luck would have it, Sir Graham ended up becoming king himself—and in so doing, single-handedly ushered in the era of the graphical adventure game.

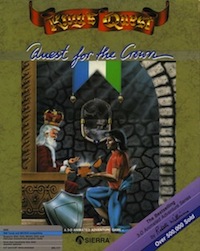

King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown, Sierra’s ground-breaking title, turns thirty this July. Easily the most ambitious (and expensive) adventure game developed as of its release in 1983, King’s Quest set the stage for a whole new kind of interactive entertainment. The game was hugely successful, came to spawn eight sequels, half a dozen spin-off “Quest” franchises, and a hugely loyal fan base. The game also launched Sierra Online into the heart of the games industry, and set the gold standard for the nascent genre.

King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown, Sierra’s ground-breaking title, turns thirty this July. Easily the most ambitious (and expensive) adventure game developed as of its release in 1983, King’s Quest set the stage for a whole new kind of interactive entertainment. The game was hugely successful, came to spawn eight sequels, half a dozen spin-off “Quest” franchises, and a hugely loyal fan base. The game also launched Sierra Online into the heart of the games industry, and set the gold standard for the nascent genre.

Adventure gaming evolved over the years. The genre peaked in the late 1990s with titles such as Gabriel Knight and Phantasmagoria —but as console gaming took over the industry, adventure games went into hibernation. Only with the advent of mobile and tablet gaming did the genre rise from the ashes; the App and Android stores are now full of classic adventure games, including ports, HD updates, and plenty of new titles. The trend has been helped along by crowd-funding: as of this writing, Kickstarter campaigns have successfully rebooted both the Space Quest and Leisure Suit Larry series, with talk of a Police Quest Kickstarter down the road. (And those are just the Sierra games. Plenty of other adventure franchises are seeing their own second coming.)

Yet despite all the ups and downs, the King’s Quest games have remained almost mythical in the annals of adventure gaming. No other series has achieved quite the same level of success: to date, the franchise includes four ultra-classic games (KQ 1-4), three point-and-click games (KQ 5-7), three visually enhanced re-releases for Mac/PC (KQ1-3), a controversial 3D game (KQ8), a five-chapter CG fan game (KQ: The Silver Lining), three separate attempts at a ninth installment, and now an upcoming reboot from Activision. The Kingdom of Daventry may have aged, but the series has most certainly endured.

Yet despite all the ups and downs, the King’s Quest games have remained almost mythical in the annals of adventure gaming. No other series has achieved quite the same level of success: to date, the franchise includes four ultra-classic games (KQ 1-4), three point-and-click games (KQ 5-7), three visually enhanced re-releases for Mac/PC (KQ1-3), a controversial 3D game (KQ8), a five-chapter CG fan game (KQ: The Silver Lining), three separate attempts at a ninth installment, and now an upcoming reboot from Activision. The Kingdom of Daventry may have aged, but the series has most certainly endured.

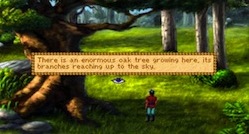

What makes this series evergreen? Truth told, the games are simple—interactive stories set in imaginative worlds like living puzzle boxes. You need to enter a castle, but there’s a dog blocking the door. So you find a stick in the forest, throw it on the roof, and voila—open sesame. That’s the genre in a nutshell, but what set this series apart were two things. First, the world of the games was amazing. They were a mash-up of fairy tales, high fantasy, ancient myth, and tongue-in-cheek humor, somehow managing to be both earnest and light-hearted, both familiar and extraordinary. This was the particular genius of Ken and Roberta Williams.

What makes this series evergreen? Truth told, the games are simple—interactive stories set in imaginative worlds like living puzzle boxes. You need to enter a castle, but there’s a dog blocking the door. So you find a stick in the forest, throw it on the roof, and voila—open sesame. That’s the genre in a nutshell, but what set this series apart were two things. First, the world of the games was amazing. They were a mash-up of fairy tales, high fantasy, ancient myth, and tongue-in-cheek humor, somehow managing to be both earnest and light-hearted, both familiar and extraordinary. This was the particular genius of Ken and Roberta Williams.

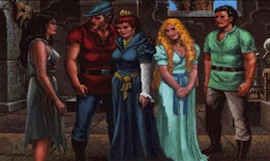

The second thing were the characters. The royal family of Daventry were perhaps the most likable protagonists in gaming history. Conventional wisdom says that good stories are rooted in conflict between the main characters. Not so with these royals. Graham, Valanice, Alexander, and Rosella were humble, thoughtful, respectful, and dedicated—and therein lay their appeal. There’s something to be said for a story in which the heroes are not soldiers, thieves, assassins, and tyrants (no offence to the Lannisters), but moms, dads, brothers and sisters, venturing into peril armed only with their hearts and minds. You rooted for these guys because you were these guys. And just like you, all they really wanted was to keep the realm at peace, and be together with each other.

The second thing were the characters. The royal family of Daventry were perhaps the most likable protagonists in gaming history. Conventional wisdom says that good stories are rooted in conflict between the main characters. Not so with these royals. Graham, Valanice, Alexander, and Rosella were humble, thoughtful, respectful, and dedicated—and therein lay their appeal. There’s something to be said for a story in which the heroes are not soldiers, thieves, assassins, and tyrants (no offence to the Lannisters), but moms, dads, brothers and sisters, venturing into peril armed only with their hearts and minds. You rooted for these guys because you were these guys. And just like you, all they really wanted was to keep the realm at peace, and be together with each other.

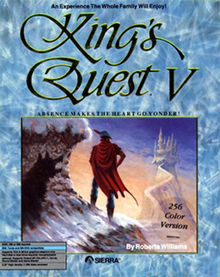

In honor of the thirtieth anniversary, I’m replaying the two best entries in the series: King’s Quest 5: Absence Makes the Heart go Yonder, and King’s Quest 6: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow. As a kid, KQ5 was my favorite. It was the first time I’d ever seen VGA graphics, and prompted me to ask my parents to upgrade my Apple IIc to a 386 PC. The story of the game was simple: Graham’s family gets whisked away by an evil wizard, and Graham sets off to find them. He wanders a landscape twenty-four screens square (not counting the infinite desert), talking with witches, beguiling woodworkers, finding needles in haystacks, and trying to traverse a mountain pass into the lands beyond. I’ll never forget the moment I finally made it out of that valley. What would I find in those snowy peaks? The answer was simple: adventure.

In honor of the thirtieth anniversary, I’m replaying the two best entries in the series: King’s Quest 5: Absence Makes the Heart go Yonder, and King’s Quest 6: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow. As a kid, KQ5 was my favorite. It was the first time I’d ever seen VGA graphics, and prompted me to ask my parents to upgrade my Apple IIc to a 386 PC. The story of the game was simple: Graham’s family gets whisked away by an evil wizard, and Graham sets off to find them. He wanders a landscape twenty-four screens square (not counting the infinite desert), talking with witches, beguiling woodworkers, finding needles in haystacks, and trying to traverse a mountain pass into the lands beyond. I’ll never forget the moment I finally made it out of that valley. What would I find in those snowy peaks? The answer was simple: adventure.

King’s Quest 6 was the most creative entry in the saga. In that game, you find a magic map that lets you teleport between the isles of an archipelago. Each island is a magical place, filled with elements of fantasy, but impenetrable until you find items on the other islands that allow you to explore deeper. For days, I tried to scale the Cliffs of Logic on the Isle of the Sacred Mountain. I was stumped—until one day I found a secret code in the user’s manual that caused hand-holds to emerge from the rocks! Finally, I ascended that cliff, and once again my imagination was set alight.

King’s Quest 6 was the most creative entry in the saga. In that game, you find a magic map that lets you teleport between the isles of an archipelago. Each island is a magical place, filled with elements of fantasy, but impenetrable until you find items on the other islands that allow you to explore deeper. For days, I tried to scale the Cliffs of Logic on the Isle of the Sacred Mountain. I was stumped—until one day I found a secret code in the user’s manual that caused hand-holds to emerge from the rocks! Finally, I ascended that cliff, and once again my imagination was set alight.

In the years since, I’ve played many kinds of games, including complex and sophisticated RPGs. But thinking about those King’s Quest games, I believe they were perfect for their time. Fighting monsters wouldn’t have made them more captivating. Powerful weapons wouldn’t have added to the excitement. The games appealed to my sense of adventure, pure and simple, and that in itself was rewarding. This is a lesson I think the game industry forgot for many years, but which is thankfully being rediscovered once more.

Not every King’s Quest game was a hit. King’s Quest VII: The Princeless Bride, a cell-shaded adventure starring Valanice (Graham’s wife), came across as too cartoony for audiences who had grown used to a more realistic style. King’s Quest VIII: Mask of Eternity, the first 3D installment in the series (and the only one to include battle elements) was criticized for meddling with the time-trusted formula. (Though the game sold twice as many copies as Grim Fandango that same year.) But despite those mishaps, the King’s Quest brand remains legendary—so much so that three different studios have tried to make a ninth installment in the last decade. The latest aborted effort was by Telltale Games, makers of The Walking Dead (the 2012 Game of the Year); the rights have now reverted to Activision, who claim to be developing their own next-generation King’s Quest game.

Not every King’s Quest game was a hit. King’s Quest VII: The Princeless Bride, a cell-shaded adventure starring Valanice (Graham’s wife), came across as too cartoony for audiences who had grown used to a more realistic style. King’s Quest VIII: Mask of Eternity, the first 3D installment in the series (and the only one to include battle elements) was criticized for meddling with the time-trusted formula. (Though the game sold twice as many copies as Grim Fandango that same year.) But despite those mishaps, the King’s Quest brand remains legendary—so much so that three different studios have tried to make a ninth installment in the last decade. The latest aborted effort was by Telltale Games, makers of The Walking Dead (the 2012 Game of the Year); the rights have now reverted to Activision, who claim to be developing their own next-generation King’s Quest game.

Given the resurgence of the genre, King’s Quest 9 may finally be on the horizon. We’ll have to see. But whatever happens, the series remains an icon of gaming’s humble roots. King’s Quest gave us dragons and ogres, yetis and mermaids, unicorns and minotaurs—and it gave us a whole new kind of adventure. These were games about family and imagination, about wit being mightier than the sword. There were about a place where anyone—even a seven-year-old sitting at a pre-historic computer—could set out on a quest, and find himself king.

Brad Kane works in the entertainment industry and is a story consultant on Universal’s upcoming adaptation of The Wheel of Time. Brad has worked at Pixar Animation Studios, DreamWorks Animation, and as a member of the video game press, where he focuses on the intersection of storytelling and interactivity. Get in touch with him if you have any questions, comments, or general thoughts on the nature of human existence.